On a hot summer day, a curbside fire hydrant has the

uncanny ability to singlehandedly activate public space. Yet, the use of hydrants for play has

historically been a major nuisance to the city – expending 25 - 1000 gallons

per minute and reducing water pressure to surrounding hydrants. Still,

these street-side amusements are a powerful and important means for the public

to access water. Our access to water is

incredibly stagnant. Most water access

is either denied (abandoned

reservoirs and blocked river access), squarely

defined (public pools) or considered

trespassing (fountains in center city provide one of the most appealing

entry points). At least one lovely

watering hole exists (devil’s pool and kitchen’s lane in the wissahickon) but

perhaps the most boundless access to water in the city is through the city’s

hydrants.

I’d like to examine possibilities for what a public pool

could be in Philadelphia. What fantastic play experiences can we conjure with

the starting point of an urban hydrant? Steam powered pistons? Kid-powered

sluice gates? Watermills? Lengthy slip and slides? I’d like to take advantage

of site topography, focusing on the northern portion of American. This is an

area where local residents have already begun colonizing vacant lots with above

ground pools (see aerial photos below). I’d also like to examine the

potentials for harvesting rainwater from roofs and cleaning it with biosand

filters (a cheap solution commonly used in the developing world for making

potable water).

Williams, Marilyn Thornton. Washing

"the Great Unwashed" Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920

(Urban Life and Urban Landscape Series). Ohio State University Press, 1991

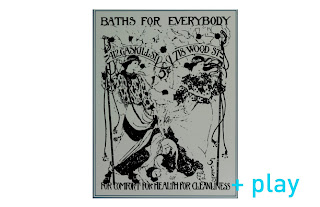

THE PUBLIC BATH MOVEMENT IN PHILADELPHIA

How can the idea of baths for cleanliness differ from the idea of baths for play?

The public bath movement between 1840 and 1890 and later bath reform in the progressive era was an attempt to equalize and sanitize conditions in the blighted neighborhoods of cities. This occurred in the aftermath of the Panic of 1837, as conditions in cities were deteriorating for the poor. “To Americans, these burgeoning slums with their poverty, vice, crime, disorder, drunkenness, and apparently unassimilable immigrants were a threat to the social fabric of American society.” (6) It was part of larger efforts towards public health reform and came out of an “American obsession with personal cleanliness” (3) The reformers were influenced by Roman public baths and the religious bathing of ancient Hebrews and Egyptians. From 13th to 17th C, medieval public baths in Europe were places of amusement subject to “antibath campaigns by the clergy” (7).

1761: plans to develop the chalybeate spring in Northern Liberties were opposed to by Protestant ministers. They opposed “erecting public Gardens with Baths and Bagnios among us. Were a Hot and Cold Bath necessary to the Health of the Inhabitants of the City, they might at a small expense be added to the Hospital… (a stop must be put to the people’s) Immoderate and Growing Fondness for Pleasure, Luxury, Gaming, Dissipation, and their concomitant Vices.”

I’d like to see whether harvested water for play could

also be directed for use by gardeners or nurseries in the area. This would be a

way of establishing a more permanent and secure space for urban agriculture

through access to water (this is a problem that has been identified by PHS and the Pubic Interest Law Center in

their work in providing information to gardeners on accessing fire hydrants and

on land security – 2 issues they face in the city)

No comments:

Post a Comment